*Image above: ELCA Presiding Bishop Elizabeth Eaton thanking Rabbi Jonah Dov Pesner, Director of the Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism and Senior Vice President of the Union for Reform Judaism. He spoke at the 2019 ELCA Churchwide Assembly.

Grace to you and peace,

from the One who is, who was, and who is to come.

Amen

On Sunday I offered more of a Bible Study lesson than I did a sermon. It is not my style. It felt awkward to me, but also necessary. The language of the Gospel of John can be jarring at times, with its regular pitting of “The Jews” against Jesus … as if it were “the Jews” who stood against everything he taught, as if “the Jews” are the enemies of all who follow Jesus, as if it were “the Jews” who killed Jesus.

Of course, this is exactly the thread that Christians have weaved for centuries. Taking the language of the Gospel of John out of context, Christians have used their political and cultural power to do horrendous things to the Jewish community – from inquisitions and pogroms, forced conversions and expulsions, scapegoating and fear mongering, terrorist violence and ghettoization.

So, what is the context for John’s language about “the Jews,” and how have Christians misused this language for evil ends? What follows is a response to that question, including much of the material that I shared in Sunday’s sermon.

Sunday's reading from John chapter 10 is fairly typical of the kind of conflict we read in John's Gospel.

22 At that time the festival of the Dedication took place in Jerusalem. It was winter, 23 and Jesus was walking in the temple, in the portico of Solomon. 24 So the Jews gathered around him and said to him, ‘How long will you keep us in suspense? If you are the Messiah, tell us plainly.’ 25 Jesus answered, ‘I have told you, and you do not believe. The works that I do in my Father’s name testify to me; 26 but you do not believe, because you do not belong to my sheep. 27 My sheep hear my voice. I know them, and they follow me. 28 I give them eternal life, and they will never perish. No one will snatch them out of my hand. 29 What my Father has given me is greater than all else, and no one can snatch it out of the Father’s hand. 30 The Father and I are one.’

31 The Jews took up stones again to stone him.

CONFLICT

Note that “the Jews” gather around Jesus (vs 24). Jesus tells them that they “do not believe” (vs 25, 26), and that they “do not belong to my sheep” (vs 26). The lines are drawn: “The Jews” don’t believe, and “the Jews” aren’t among the flock for whom Jesus is the Good Shepherd (in John chapter 10 Jesus uses various images of shepherd and sheep to describe his relationship with his people). This framing of the tension between “the Jews” and Jesus is found throughout the Gospel, and especially in Chapter 8 and again in the Passion narrative.

CONTEXT

The Gospel of John was probably written at the end of the first century, around the year 90. This would be approximately twenty years after the Roman occupation forces destroyed the Jewish temple in Jerusalem, and approximately 60 years after the crucifixion of Jesus. For more than a generation Jewish Christians lived and worship with their fellow Jews. They shared synagogue and temple life with the broader Jewish community, but the Jewish Christians also maintained distinct teachings and practices based on their faith that Jesus is the Messiah.

It is important to note that variation in religious practice and belief were not – and are not, to this day – uncommon. No religious group is a monolith. Diversity within a religious group sometimes spins off to create new a sect and tradition within, or apart from, the established religious group. The community of faith that sprung up around Jesus wasn’t necessarily unique in that regard.

Now, this was a time of great tension within occupied Israel. Pagan Roman forces occupied and controlled what Jews understood to be their Promised Land given to them by God. For several hundred years they had been controlled by outsiders – Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, and Romans. Their temple had been destroyed, rebuilt, desecrated by the installation of pagan idols, and then destroyed again. Splintering religious movements, like that which formed around Jesus, risked spiritual and social upheaval that was unacceptable to the religious elite whose job it was to maintain the faith and keep nice with the Roman occupiers.

To be clear, the claim that Jesus is the Messiah is an earthshatteringly major claim to make within the context of Jewish faith and practice. The mainstream Jewish leadership did not accept this claim, finding this spurious teaching and movement dangerous to Jewish unity and Israel’s security. Yet John does not write that “the Jewish leadership,” or “the Sanhedrin” rejected Jesus. He writes of “the Jews” and their rejection of Jesus.

Why does John use this language? Writing in the late first century, John is part of a small Christian Jewish congregation that was likely expelled from synagogue life, cut off from families, and otherwise exiled from the broader Jewish community. As personae non gratae, they girded themselves with an “us-vs-them” rhetoric to make sense of their situation. Such boundary-creating rhetoric was actually a common genre or style in the first century Roman-influenced world. John labeled the mainstream Jewish leaders as “the Jews” who stood in opposition to Jesus and his followers. This “us-vs-them” language and tone come out in John’s telling of the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

Thus, John’s Gospel is written within the context of intra-Jewish struggles for identity, authenticity, and legitimacy within the Jewish community during a time of traumatic Roman occupation and violence. We must understand this language as a function of that struggle for Jewish identity and not as something intentionally antisemitic. The first generations of Christ-followers were a small Jewish faction, and this was their language.

A representation of the Spanish Inquisition

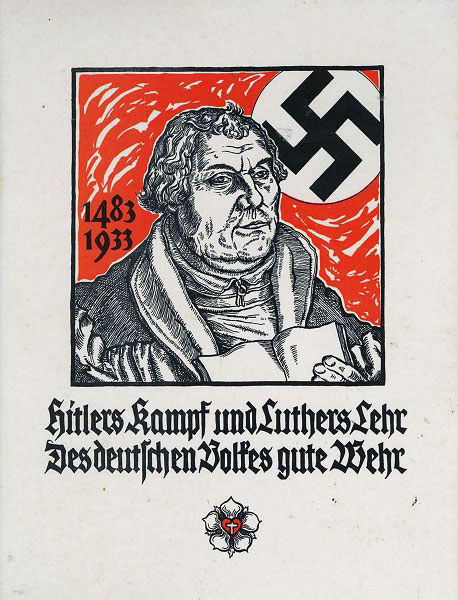

"Hitler's fight and Luther's teaching are the best defense for the German People" Source: FacingHistory.org

LEGACY

The problem with this language becomes obvious centuries later. Christianity takes hold in Gentile regions, among people who are neither ethnically nor spiritually Jewish. As such, these non-Jewish Christians don’t have the deep connection with established Jewish life and tradition that the first generations of Christians did – that John the Gospel writer did. When these later Gentile Christians read the Gospel of John, they see language about “the Jews” and don’t see in it their kin. They do not interpret these texts as part of an intra-Jewish struggle between co-religionists. Instead, Gentile Christianity comes to see Jews as “the other.” They accept John’s characterizations of “the Jews” as applying not to a small group of religious leaders but to the Jewish population as a whole.

Paradoxically, Christianity becomes the religion of the empire over time. It was the Roman Empire who put Jesus and some of his first followers to death. Now, Christianity was using the sword and the power of the empire to spread Christianity as a unifying force within their expansive realm. Joining Gentile Christian misreading of the Gospel of John with the authority to direct armies and execute justice, Christians began to persecute Jewish communities for perceived crimes, both historic and in their present day.

800 years ago the English Church expelled all Jews from England. The Spanish Inquisition forced thousands of Jews to convert to Christianity, to flee Spain, or to be executed. For centuries throughout Europe Christian terrorist mobs and state violence would unleash violence in Jewish communities. Was this constant? No, but it was a favored tactic when political, economic, or public health crises – think of famines and pandemics – threatened stability. Scapegoating Jews was a convenient way to deflect criticism and place blame on others.

As part of this tradition Martin Luther – the namesake for our own tradition within Christianity – wrote a wretched treatise in 1543 called, “On the Jews and their Lies,” in which he countenanced the burning of Jewish synagogues in Germany. 400 years later such hateful rhetoric made it onto the lips of Nazi propagandists, fueling the evil machinations of the Third Reich.

Accordingly, it [is a serious matter] to save our souls from the Jews, that is, from the devil and from eternal death. My advice, as I said earlier, is:

First, that their synagogues be burned down, and that all who are able toss in sulphur and pitch; it would be good if someone could also throw in some hellfire. …

Second, that all their books—their prayer books, their Talmudic writings, also the entire Bible —be taken from them, not leaving them one leaf, and that these be preserved for those who may be converted. …

Third, that they be forbidden on pain of death to praise God, to give thanks, to pray, and to teach publicly among us and in our country. They may do this in their own country or wherever they can without our being obliged to hear it or know it.

Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Vol. 47: The Christian in Society IV, ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, and Helmut T. Lehmann, vol. 47 (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1999), 285–286.

RESPONSE

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, our national denomination, unequivocally repudiated Luther’s antisemitism in a Declaration to the Jewish Community in 1994. The churchwide council updated and reaffirmed the statement in 2021. This statement is powerful, and it is featured prominently in the National Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC. Repentance matters – not just before God, but before our neighbors.

We Lutherans should commit ourselves to annual days of lament and repentance for the evil done by our ancestors, and the enduring legacy their evil continues to exhibit. Perhaps such lament and repentance can take place in conjunction with International Holocaust Remembrance Day (January 27), or with Israel’s Holocaust Memorial Day (27th day of Nisan, which falls in April or May of the Gregorian calendar). I’ll mark my calendar for us to observe this remembrance next January.

PROMISE

The Good News in all this is that we know the broad arc of the Scripture’s story. Our God is a God of mercy and grace, who chose the small tribe of Israel to be a priestly people before the world. This God rescued them from slavery in Egypt, gave them a blessed way of life, and a land to dwell in God’s presence. Throughout their sufferings and trials, our Lord sent to them prophets to speak hope and promise in their midst, and to guide them into righteous living.

In the fullness of time we Christians recognize that from the Jews came a Messiah, a teacher, whose promises and wonders are gifts of God. We see in Jesus’ miracles and teachings echoes and extensions of what we see and revere in the long history of God’s blessings in and through the People Israel. We acknowledge that in Christ we have life, and have it abundantly. And because of Jesus, we have hope for a new life and a new creation, and the promise of a holy way of living here that follows him in faithful service and love for our neighbor.

There is nothing in Christian Scripture that can be faithfully construed to work evil toward anyone. Such interpretations and misuses of Scripture are the work of evil, and must be rejected by all who bear Christ’s name. Woe to any who would use words of life to bring about suffering and death, particularly toward the first people to hear the word of God, but indeed for all people. Blessed are those who receive in Scripture and our Christian tradition the promise of faith and the expectation of resurrection for us and for this world that God so loves.

Beloved, let us love one another as we have been loved.

The peace of Christ be with you.

Pastor Chris Duckworth

Worshipping with our Bodies

February 16, 2024 Posted By: Pastor Chris Duckworth Ministry Blog bodyWorshipping with our Bodies Among Western Christians there can be...

From Love to Love: God’s Passion for All People

February 5, 2024 Posted By: Pastor Chris Duckworth Ministry Blog lentFrom Love to Love: God's Passion for all People Lent,...

Job Opening: Parish Administrator

January 17, 2024 Posted By: Pastor Chris Duckworth Ministry Blog administratorJob Opening at New Joy Lutheran The New Joy Personnel...